In Kyoto, the unique style of speech known as Kyokotoba has been used for generations. Not only do the expressions differ from standard Japanese, but the intonation also has a distinctive quality that gives off an elegant and refined impression, doesn’t it? This article introduces the basics of Kyokotoba, including key characteristics, essential greetings, and useful phrases for sightseeing—all in a convenient list.

*By purchasing or reserving products introduced in this article, a portion of the sales may be returned to FUN! JAPAN.

😄Enjoy a more convenient trip to Japan with NAVITIME eSIM!👉Click here

🚅Book your Shinkansen ticket with NAVITIME Travel! 👉 Click here

What kind of dialect is Kyokotoba (Kyoto language)?

"Kyokotoba" is spoken in the Kyoto area. Kyoto served as Japan’s capital from the Heian period to the Meiji Restoration. While it is now considered a dialect, at the time, Kyokotoba was the "standard language" of Japan.

Unlike the more commonly recognized Kyoto dialect (Kyotoben), Kyokotoba refers to the everyday language used by people who have long lived in Kyoto. This speech style conveys warmth, politeness, and attentiveness, reflecting the city’s deep historical and cultural roots.

However, just like other dialects, some parts of Kyokotoba have gradually faded from everyday use due to societal and lifestyle changes. Examples include しょうびんな (meaning “poor-looking”), なんぎな (meaning “troublesome”), and けなりい (meaning “enviable”).

Two Types of Kyokotoba

Kyokotoba is generally divided into two categories: Gosho kotoba, used by court ladies serving in imperial or noble households, and Machikata kotoba, used in the streets as everyday language. Furthermore, Machikata kotoba includes more specific subgroups, such as Shokunin kotoba (artisan speech) in Nishijin, known for Nishijin textiles; Hanamachi kotoba (entertainment district speech) in Gion; and Muromachi shōnin kotoba (merchant speech) in the Muromachi wholesale district.

Commonly Heard Kyokotoba Phrases

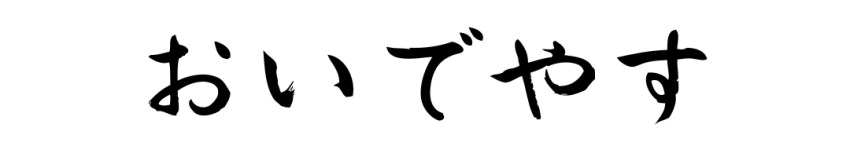

While sightseeing in Kyoto, you may frequently hear おおきに(okini), which means “thank you.” The phrase comes from 大きにありがたし(okiniarigatashi), meaning “deeply thankful.” When entering souvenir shops and similar places, you might also hear おいでやす(oideyasu) or おこしやす(okoshiyasu)—both are welcoming phrases meaning “welcome” or “please come in.”

Characteristics of “Kyokotoba”: A Thorough Comparison with Standard Japanese!

"Kyokotoba" has distinctive features in intonation, sentence endings, and expressions.

Feature 1: Indirect and Euphemistic Expressions

Rather than stating things directly, Kyokotoba often uses soft, euphemistic phrasing. For example, instead of saying “I think that’s good” directly, people might say “Sore ga ee no to chigaimasu yaroka” (Couldn’t that be good?). Other examples include Omoshiroi hito dosuna meaning “He’s a bit unusual,” and Suki ni shahattara yoroshii yan subtly meaning “Please don’t get me involved.”

Feature 2: Unique Styles Like Reduplication, Extended Vowels, and ‘U-onbin’

Kyokotoba uses reduplication to emphasize adjectives, such as takai takai (very tall) or atsui atsui (very hot). This is known as jōgo (reduplication). Also, words like ka (mosquito), ki (tree), and ke (hair) are pronounced with elongated vowels as かあ(kaa)」, きい(kii), and けえ(kee), respectively—these are examples of chōongo (long-vowel words). There's also u-onbin, where the final vowel becomes “う(u),” like marui (round) becoming まるう(maru), or karai (spicy) becoming かろう(karo).

Feature 3: Unique Vocabulary

Some Kyokotoba words have direct counterparts in standard Japanese, but many are entirely different. For instance, おおきに(okini)means “thank you,” いけず(ikezu)means “mean or spiteful,” and ほかす(hokasu)means “to throw away.” In place of the imperative “do it” (shinasai), Kyokotoba would say しよし(shiyoshi).

Feature 4: Different Intonation

The intonation in Kyokotoba is distinctive. For example, inありがとう(arigato), the standard accent falls on り(ri), while in Kyokotoba the stress is on とう(to). The overall rhythm is more melodic and gentle, giving an impression of calm refinement.

Feature 5: Unique Sentence Endings

Honorific expressions also differ. While standard Japanese adds される(sareru)to verbs to show respect, Kyokotoba uses しはる(shiharu)instead.

It’s also common to hear sentence endings like やす・おくれやす(yasu・okureyasu). For instance, 掃除しておくれやす(souji shite okureyasu) means “Please clean.” Doesn’t it sound softer than the standard form?

Also, the ~へん(hen) is used in negative forms. 行かへん(ikahen/with a falling tone) means “I won’t go,” but 行かへん? (with a rising tone) becomes “Won’t you come?”

Feature 6: Words with Multiple Meanings

Another characteristic of Kyokotoba is that some words have several meanings. For example, the words below can have 4 to 5 different interpretations.

"えらい(erai)"

- Serious, extreme, terrible

- Outrageous

- Great, admirable

- Tired, hard, painful

"せんど(sendo)"

- A lot

- Fully

- Often

- For a long time

"あかん(akan)"

- Not allowed

- Not effective

- Useless

- Weak

- Won’t open

Feature 7: Beautiful and Elegant Kyokotoba

People in Kyoto try to avoid rough speech and aim to use polite and refined language. The command expression "待ってて!(mattete! / 待ってほしいという意味)" becomes "待っててや(matteteya)」" by adding the softening suffix "や(ya)", which gives it a gentler impression.

18 Kyokotoba You’ll Want to Try, Like “Ōkini” and “Hannari”

Here are some practical Kyokotoba phrases that you may want to try using during your stay in Kyoto.

5 Greeting and Basic Conversation Phrases

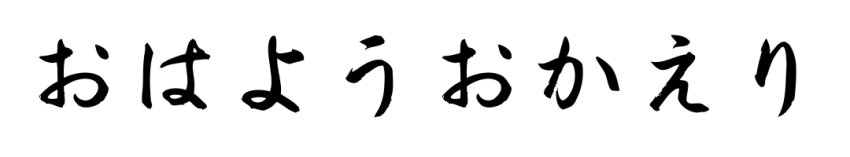

1. おはようおかえり(ohayokaeri)/ Meaning: Take care

When sending off a child (or student) going to school, parents usually say "Itterasshai" in standard Japanese, but in Kyoto, they say "おはようおかえり". Here, "おはよう" means "early", and the phrase as a whole conveys a wish for the person to "return safely and peacefully". When speaking to someone commuting to work, a more polite version is used: "おはようおかえりやす(ohayookaeriyasu)", with the respectful suffix "やす(yasu)".

2. おたのもうします(otanomoshimasu)/ Meaning: Please

"おたのもうします" means "please". The word "tanomu" (to request) is derived from the act of putting hands together in prayer. It’s used in phrases like "これからもおたのもうします(korekaramo otanomoshimasu)" (Please continue to support me). Even today, it is commonly used by maiko and geiko in Kyoto's entertainment districts.

3. めっそうな(messona)/ Meaning: You’re welcome

This means "you’re welcome" or "not at all". For example, if someone says "You’re so good at studying, I’m jealous", the response might be "めっそうな".

4. すんまへん(summahen)/ Meaning: Sorry

Used in contexts like "いつもお世話になりすんまへん(itsumo osewaninari summahen) or "お先に失礼してすんまへん(osakini shitsureishite summahen)" , it means "sorry". Derived from the idea of one’s heart being unsettled, it is also used to express gratitude in addition to apologies.

5. かんがえときます(kangaetokimasu)/ Meaning: I’ll pass

While it literally means "I’ll think about it" in standard Japanese, in Kyokotoba it actually means "I’ll pass". Rather than saying it directly, it softens the refusal by implying that "thinking about it" means deciding not to.

6.はんなり(hannari)/ Meaning: Graceful and elegant

Outside the Kansai area, "はんなり" is often imagined to mean "graceful" or "laid-back", but in Kyokotoba it means "graceful, bright, and elegant". It is often used to describe clothing or appearances.

7 Useful Phrases for Shops and Tourist Spots

1. おいでやす(oideyasu)/ Meaning: Welcome

This is a phrase you’ll often hear when entering souvenir shops in Kyoto. It means "Welcome and thank you for coming."

For a more polite version, people say "おこしやす(okoshiyasu)". Other expressions include "おいでやしとくれやす(oideyashitokureyasu)" and "ようこそおこしやしとくれやした(yokoso okoshiyashitokureyashita)".

Just like "おいでやす", honorific expressions that use the prefix "お(o)" and suffix "やす(yasu)", such as "お読みやす(oyomiyasu)" and お書きやす(okakiyasu)", are common in Kyokotoba.

2. おこしやす(okoshiyasu)/ Meaning: いらっしゃいまse (more polite)

This is a more respectful version of "おいでやす(oideyasu)". "Okoshiyasu" is a shortened form of "ようお越しやした(yo okoshiyashita)", which is a more formal way of saying "welcome". It’s often used for guests who made reservations in advance or those who are being especially welcomed.

3. おおきに(okini)/ Meaning: Thank you

"おおきに" is used to express gratitude. It originally came from "おおきに(大変、大いに)ありがとう(okiniarigato)" (meaning "thank you very much"), and over time, the "ありがとう(arigato)" part was dropped. Today, just "おおきに" is used to mean "thank you".

4. うつる(utsuru)/ meaning: to become, to harmonize

If a shop staff member says, "その洋服の柄はよううつってますな(sono yofukunogaraha youtsuttemasuna)", they mean "It really suits you." The word "うつる" originally means "to be reflected" or "to appear in one’s eyes", and in this context, it implies something that suits someone well.

5. ごめんやす(gomenyasu)/ Meaning: Hello

A simple greeting used like "Excuse me for a moment." It can be heard when entering or leaving a house or shop, or when passing in front of someone, such as in "ごめんやす、奥さんいらっしゃいますか(gomenyasu okusan irasshaimasuka)?" . It’s a more polite version than "すんまへん(sunmahen)".

6. よろしゅうおあがり(yoroshuoagari)/ Meaning: Thank you very much for your call

This is a phrase used in response to "Gochisōsama" (Thank you for the meal). It carries the meaning of "Thank you for enjoying the meal."

5 phrases to express emotions and situations

1. かんにんえ(kannine)/ Meaning: I'm sorry. Please forgive me

"かんにんえ" means "I'm sorry" or "Please forgive me." It can also be used without the "え(e)" as in "えらい遅うなってしもて、かんにん、かんにん(erai osonatteshimote kannin kannin)" (Sorry I'm really late, please forgive me).

2. おきばりやす(okibariyasu)/ Meaning: Please do your best

"よう勉強しはりますな、おきばりやす(yobenkyoshiharimasuna okibariyasu)" means "You're studying hard. Keep it up!" The word originates from "kibaru", which means "to tense up and make an effort". Like "おいでやす" and "おこしやす", this is another polite expression with the prefix "お(o)" and suffix "やす(yasu)".

3. うれこい(urekoi)/ Meaning: Happy

"明日は誕生日。うれこいな(ashitaha tanjobi urekoina)" means "Tomorrow’s my birthday. I’m happy!" The suffix "~こい(koi)" is also used in other adjectives like "ひやこい (hiyakoi / cold)", "まるこい (marukoi / round)", and "こまこい (komakoi / detailed)".

4. ようすする(yosusuru)/ Meaning: To act pretentious

Used in phrases like "あの人は男の人の前では、ようすするのや~(anohitoha otokonohitonomaedeha yosusurunoya~)", it implies "She acts pretentious around men." "Yōsu" means "appearance or demeanor", so the phrase means "to put on airs" or "act formal".

5. へたばる(hetabaru)/ Meaning: To collapse or sit down from exhaustion

Used in situations like "山登りの途中でへたばってしまったわ(yamanoborino tochude hetabatteshimattawa)" (I collapsed halfway through the mountain climb). "へた(heta)" means "flat", and "ばる(baru)" means "to stretch". Variations include "へたる(hetaru)" and "へちゃばる(hechabaru)". It can also describe being down with a cold, like "Kaze wo hiite hetatteru" (I’m down with a cold).

The Hidden Meaning Behind 'Would You Like Some Bubuzuke?' and Kyoto’s Culture

These days, when someone says "Bubuzuke demo dō dosu?" (Would you like some rice with tea?), it's often interpreted as a polite way of saying "You’ve stayed long enough; it’s time to go." But that wasn’t the original meaning.

In Kyoto, it’s customary to prepare a proper meal when inviting guests. If a host wasn’t prepared, offering "bubuzuke (ochazuke)" was a polite way to say "I’m sorry, I’m not ready to offer proper hospitality." The guest, understanding the host’s feelings, would reply "Maybe next time" and leave. This gentle exchange reflects Kyoto’s culture of mutual consideration.

"よろしい" Can Mean "Whatever"!?

Some Kyokotoba phrases require understanding the meaning behind the words rather than just the words themselves. For example, "よろしい(yoroshii)" normally means "good", but in Kyokotoba, it can mean "どうでもよろしい(doudemo yoroshii)". It’s used to imply indifference or dismissal.

Similarly, "おおきに(okini)", usually meaning "thank you", can also imply a polite refusal. For example, it might be used in a situation like "Thank you for the invitation, but I’ll pass."

Other Indirect Expressions to Watch Out For

Take the exchange: "How’s your health?" / "ぼちぼちですわ(bochibochidesuwa)". "Bochi bochi desuwa" implies a reluctance to give a clear answer, like "I’m doing okay, I guess."

Or when someone says "面白い人どすな(omoshiroihitodosuna)", it may sound like "You're an interesting person", but often carries the nuance of "You’re kind of odd." "好きにしゃはったらよろしいやん(sukini syahattara yoroshiiyan)" sounds like "Do as you like", but it actually means "That’s your problem, don’t drag me into it."

What Does "一見さんお断り" Really Mean? Kyoto's Spirit of Hospitality and Language

The phrase "Ichigensan okotowari (一見さんおことわり)" means that first-time or unknown visitors are not permitted; only regular customers or those who have been introduced by existing patrons can enter. At first glance, this might seem _exclusive_ or _unwelcoming_, and many people may interpret it that way. However, the true meaning reflects the establishment's belief that unless they know in advance what a guest likes or dislikes, they cannot provide heartfelt _omotenashi_, or Japanese-style hospitality. In some cases, the person introducing the guest may be asked in advance about the visitor’s food preferences, interests, and tastes. Based on that, not only the food but also the tableware, hanging scrolls, and interior decorations might be carefully selected to suit the guest.

Behind the words "一見さんお断り" lies a sincere desire: even if a guest is a first-time visitor, the host wants to offer them the best hospitality possible and make a meaningful connection.

[Bonus Section] 5 Recommended Dramas, Films, and Anime Featuring "Kyokotoba"

Here are five titles where you can experience Kyokotoba through stories and characters:

"The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House"

Manga publication period: December 28, 2016 –

This story follows Kiyo, a girl who prepares meals at an okiya (a geisha house) in Kyoto. It portrays the daily lives of maiko living together in the hanamachi (geisha district). It has been adapted into an anime on NHK E-TV and a live-action drama on Netflix.

👉 【Yahoo! Shopping】Purchase "The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House"–related products

"Deaimon"

Manga publication period: April 2016 –

Nagomu Irino returns to his family's traditional Kyoto wagashi (Japanese sweets) shop after 10 years when his father is hospitalized. However, rather than being named the successor, he's asked to act as a father figure to a young girl named Itsuka Yukihira, who’s expected to inherit the shop. The heartwarming story unfolds gently in Kyoto.

👉 【Yahoo! Shopping】Purchase "Deaimon" manga

"Onmyoji I & II."

Theatrical release dates: October 6, 2001, and October 4, 2003

These films are based on the novel "Onmyoji", which follows the mystical adventures of Abe no Seimei, an onmyoji (court diviner) in the Heian period. Alongside samurai Minamoto no Hiromasa, Seimei tackles mysterious cases set in ancient Kyoto.

👉 【Yahoo! Shopping】Purchase "Onmyoji I & II" DVDs

"Lady Maiko"

Theatrical release date: September 13, 2014

A musical-style film set in Kyoto about a young girl striving to become a maiko. The movie blends singing and dancing with a heartfelt narrative. A novelized version directed by Masayuki Suo is also available.

👉 【Yahoo! Shopping】Purchase "Lady Maiko"–related products

"I Tried Living in Kyoto for a Bit"

Aired: 2022

The drama follows a woman who, while pursuing her dream of becoming a designer in Tokyo, suffers burnout and decides to spend time at her grand-uncle’s machiya (traditional townhouse) in Kyoto. Unlike typical tourism stories, it explores a Kyoto known only to locals and presents a relaxing journey of self-discovery.

👉 【Yahoo! Shopping】Purchase "I Tried Living in Kyoto for a Bit"–related products

Supervised by: Reiko Tanahashi

Head of Kyokotoba no Kai, a civic group based in Kyoto. She has dedicated herself to passing down the living language of Kyokotoba, which has over a thousand years of history. She leads regular meetings on the 2nd and 4th Tuesdays of each month and holds outreach classes at elementary schools, junior high schools, universities, children's centers, and welfare facilities. She also hosts the radio program "Weekly Kyokotoba News", and appears on YouTube in "Manga de Kyokotoba", among other activities to spread the beauty of Kyoto’s language.

Comments