Nohgaku, one of Japan’s traditional performing arts alongside Kabuki and Bunraku, is a stage art that combines the silent tension of Noh with the human warmth and humor of Kyogen.

Perfected during the Muromachi period, Nohgaku boasts a history of over 600 years and has been passed down to the present day as a symbol of Japanese aesthetics and spiritual culture.

This article will clearly explain the history of Nohgaku, its representative plays, the roles such as Shite and Waki, and key points to know when watching a performance. We will thoroughly introduce the charm of this traditional art so that even first-time viewers can enjoy Nohgaku with peace of mind.

🎫 Kabuki Viewing Ticket with English Subtitle Guide & Merchandise (Sunrise Tours)

*If you purchase or reserve products introduced in this article, a portion of the sales may be returned to FUN! JAPAN.

What is Japan’s Traditional Performing Art “Nohgaku”? History, Features, and the Differences Between Noh and Kyogen

Nohgaku (能楽) is a collective term for two performing arts, “Noh” (能) and “Kyogen” (狂言), and is one of Japan’s most representative traditional arts. Its origins can be traced back to Sangaku (散楽), which was introduced during the Nara and Heian periods, and Sarugaku (猿楽), which developed in the Kamakura period.

Noh and Kyogen are performed on the same Noh stage, each expressing different aspects, and have been passed down for over 600 years as arts that symbolize Japanese culture.

What is Noh?

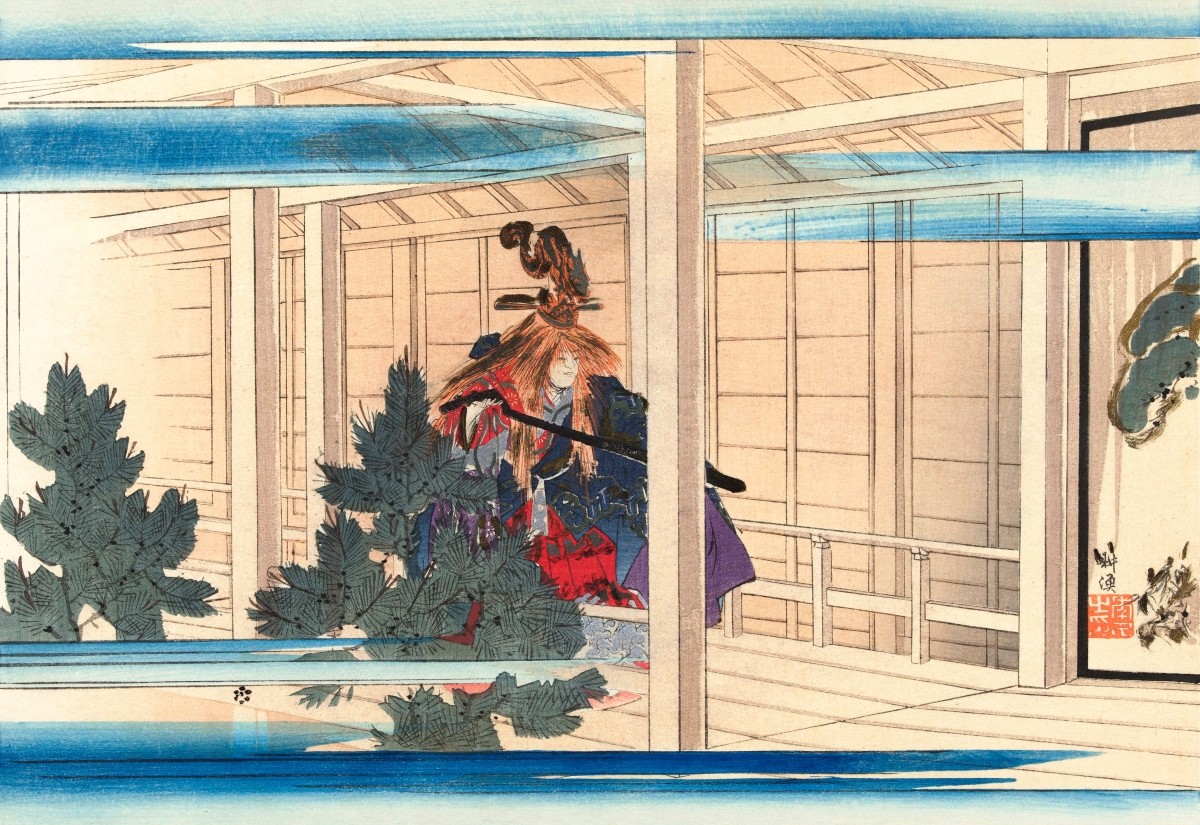

Noh is a classical Japanese performing art perfected during the Muromachi period (1336–1573). Today, about 240 plays are performed. Using Noh masks and gorgeous costumes, Noh expresses deep human emotions such as sorrow, anger, passion, and love through elegant dance and chanting (謡 / utai). Characters include deities, spirits, women, demons, and more, each portrayed with specific masks and costumes.

What is Kyogen?

Kyogen is a dialogue-centered comedy that was established in the Muromachi period. It is a stage art full of humanity, often based on the daily lives and folktales of common people. Inheriting the comic elements of Sarugaku, Kyogen features charming and unique characters who create a relaxed and cheerful atmosphere on stage.

Kyogen is often inserted between Noh plays as “ai-kyogen,” which explains the background of the story or eases the tension of the audience. On the other hand, when Kyogen is performed independently, it is called “hon-kyogen.”

The History of Nohgaku: From Sarugaku to Nohgaku

Sarugaku, the origin of Nohgaku, developed from comic performances and monomane (comedic impersonation or mimicry), and in the late Kamakura period, a magical performance called “Okina Sarugaku” associated with Shinto rituals was born. Later, in the Nanbokucho period (1336–1392), Noh began to be performed by Sarugaku troupes (entertainment groups), and during the Muromachi period, the father and son Kan’ami and Zeami greatly enhanced its artistry, laying the foundation for modern Nohgaku.

Meanwhile, Kyogen, which inherited the comic elements of Sarugaku, was also established in the Nanbokucho period and developed alongside Noh. In the Muromachi period, both arts were supported by the samurai and aristocracy, and in the Edo period, Nohgaku was officially designated as the shogunate’s ceremonial music (式楽 / shikigaku), performed at shogunal ceremonies and other official events.

The form of Noh as we know it today was also established in the Edo period, when the repertoire and production methods were organized and systematized.

From the mid-Showa period onward, the artistic value of Kyogen has also been highly regarded, and performances featuring only Noh or only Kyogen have become increasingly common. In 2008, Nohgaku (Noh and Kyogen) was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and is now highly esteemed both in Japan and abroad as a representative traditional performing art of Japan.

Kan’ami and Zeami: The Founders of Noh

Kan’ami led a troupe of Sarugaku performers during the Muromachi period, incorporating elements of Dengaku* and other popular performing arts of the time. He developed Sarugaku Noh into a highly artistic stage performance, laying the foundation for Noh as we know it today.

It was his son, Zeami, who further refined Noh. Zeami perfected the style of “Mugen Noh” (夢幻能), which excels in psychological expression, and created many Noh scripts rich in literary quality by incorporating techniques from waka and renga poetry.

Furthermore, Zeami authored theoretical works such as the seminal treatise “Fūshikaden (風姿花伝 - The Flowering Spirit),” systematizing the aesthetics and performance theory of Nohgaku and leaving a profound influence on later generations.

*Dengaku (田楽): A Shinto ritual to pray for a good harvest. It became a form of entertainment during the Heian period and is a traditional performing art.

📚Read “Fūshikaden” (Yahoo! Shopping)

Things to Know Before Enjoying a Nohgaku Performance

A typical Noh performance lasts about 60 to 90 minutes, while Kyogen lasts about 15 to 30 minutes. There are formats where one Noh and one Kyogen piece are performed together, or where Noh and Kyogen are performed alternately.

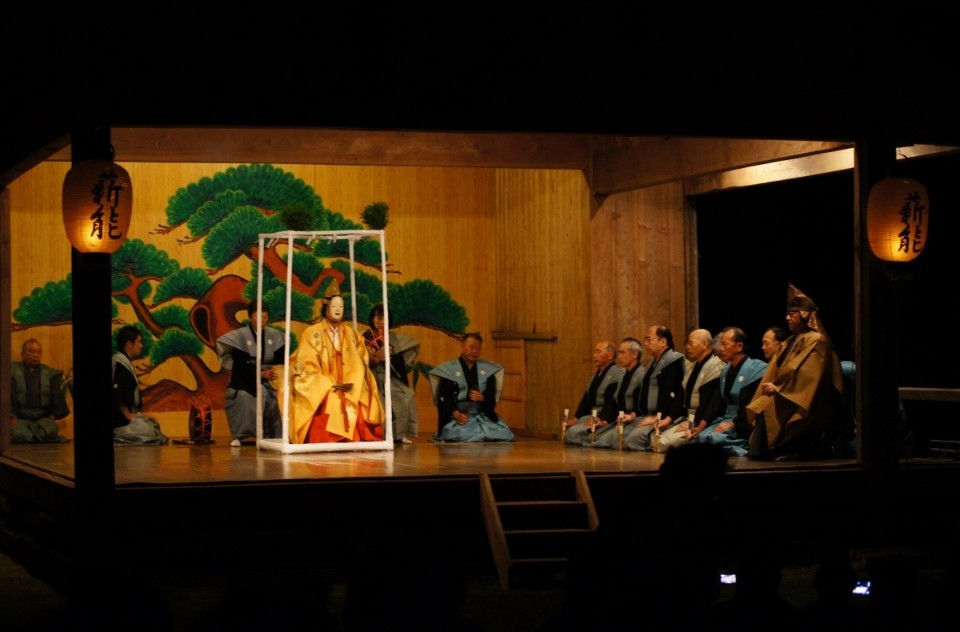

The most distinctive feature of the stage is that there is no elaborate lighting or stage equipment. Instead, the unique structure of the Noh stage—such as the backdrop painted with a pine tree and the hashigakari (橋掛かり - bridgeway)—is used to express the world of the story through acting, chanting, and musical accompaniment. The audience enjoys the performance by using their imagination, guided by the actors’ movements and the music.

Types of Roles in Noh

There are four main roles in Noh: Shite-kata (シテ方), Waki-kata (ワキ方), Kyogen-kata (狂言方), and Hayashi-kata (囃子方). Hayashi-kata is further divided into Fue-kata (笛方 - flute), Kotsuzumi-kata (小鼓方 - small hand drum), Otsuzumi-kata (大鼓方 - large hand drum), and Taiko-kata (太鼓方 - stick drum). These roles are strictly specialized, and it is rare for a performer to take on more than one role.

Additionally, each role has multiple schools (流派 / ryūha), and the combination of schools determines the organization of the performance.

Shite-kata

The actor who plays the main role, the “Shite.” The Shite usually wears a Noh mask and portrays not only living humans but also spirits, gods, demons, and other beings. A distinctive feature is the transformation of the character between the first act (前場 / maeba) and second act (後場 / nochiba).

Shite-kata also includes supporting roles such as Tsure (ツレ - companions), Jiutai (地謡 - chorus), Kōken (後見 - stage assistants who manage costumes, props, and serve as understudies), and those who create stage props.

Waki-kata

The “Waki-kata” plays the counterpart to the Shite, drawing out the main performance. They usually portray real-life adult men such as monks, Shinto priests, or samurai, and typically perform without wearing a mask.

Kyogen-kata

“Kyogen-kata” are actors who perform Kyogen. In Aikyogen (間狂言 - interlude Kyogen), roles are divided according to the play. The Katari-ai (語りアイ) connects the first and second acts through dialogue with the Waki after the Shite exits the stage.

“Ashirai-ai” (アシライアイ) means “supporting role,” assisting the Waki and facilitating the progression of the play. As attendants to the Waki, they interact with other actors to advance the story.

Kyogen-kata add variety to the overall flow of Nohgaku and help make the performance more accessible and understandable to the audience.

Hayashi-kata

The hayashikata are divided into flute players, small hand drum players, large hand drum (ōtsuzumi) players, and taiko players, and are responsible for the music in Noh. The performers sit at the back of the stage in the hayashi-za and play their instruments; depending on the piece, the taiko may not be included.

They play an important role in creating the atmosphere and tension of Noh, and together with the chanting (謡), they help shape the world-building of the stage.

Types of Noh Performances: The Five Categories by the Role of the Shite, "Goban-date"

One of the performance formats in Noh is called "Goban-date" (五番立), in which the plays are divided into five types according to the roles and tone of the piece, and one play from each category is performed. This format was established in the Edo period and was used when Noh was systematically performed from morning until evening.

Nowadays, it is rare to perform all five categories in a single day, but this classification remains important for understanding Noh plays.

First Category: "Wakinoh-mono" (脇能物)

These are Noh plays in which deities or retainers serving the emperor appear, and the gods bless the peace of the world or recount the origins of shrines and temples. Also called "Waki Noh," these plays are characterized by their strong celebratory nature.

Second Category: "Shura-mono" (修羅物)

These Noh plays feature the spirits of warriors who died in battles such as the Genpei War, depicting their suffering in the realm of shura (the world of fighting). Because they deeply express the impermanence of life and death against the backdrop of war, they are called "Shura-mono."

Third Category: "Kazura-mono" (鬘物)

Many of these plays feature female spirits from classical literature, flower spirits, or celestial maidens as the shite, showcasing elegant songs and dances. Kazura-mono are rich in splendor and lyricism, and include famous works such as "Hagoromo" (羽衣 - The Feather Mantle) and "Kakitsubata" (杜若 - Kakitsubata 'The Iris'), making them a representative genre of Noh.

Fourth Category: "Zatsu-noh" (雑能)

This is a diverse group of works that do not fit into the above four categories. It includes plays about madwomen, demon women, and realistic domestic stories, and is characterized by its wide range of content.

Fifth Category: "Kirinoh-mono" (切能物)

These Noh plays feature non-human shite, such as demons, animal spirits, vengeful spirits, yokai, or bodhisattvas. Also called "Kiri Noh," these plays are often dynamic and powerful, and were traditionally performed at the end of a program.

Types of Noh Performances: Genzai Noh and Mugen Noh

In addition to the "Goban-date" classification, Noh can also be divided into "Genzai Noh" (現在能) and "Mugen Noh" (夢幻能) based on the style of production and the nature of the characters.

Genzai Noh is structured around real people in the present world, with most of the characters depicted as living humans.

On the other hand, in Mugen Noh, the shite is a spiritual being. The typical structure is that the shite appears before the waki, who has visited a famous place, and in the first half tells the story or history of the place, then disappears, only to reappear in the second half in their true spiritual form and perform a dance.

Afterwards, these events end as if they were a "dream" (夢 can be read as 'yume' or 'mu'), creating a sense of impermanence and mysterious beauty. This is the origin of the name "Mugen Noh."

Types of Kyogen Performances: Classification by the Role of the Shite

In Kyogen, the roles often do not have specific names, and the shite is usually a character reflecting the common people or social classes of the Muromachi period.

The most representative is "Shomyo Kyogen" (小名狂言), in which the shite is the Taro Kaja*. Other categories include "Daimyo Kyogen" (大名狂言), where a feudal lord (Daimyo) is the shite, stories revolving around a son-in-law, and plays featuring demons or gods of fortune, among many other genres.

Kyogen depicts the common touch and satire of each role, offering a familiarity that contrasts with the solemnity of Noh.

*Taro Kaja (太郎冠者): "Taro" (太郎) means "first," and "Kaja" (冠者) means "young man," referring to the chief servant. He is a popular character representing Kyogen.

Representative Works of Noh

"Okina" (翁)

“Okina” is a ritualistic Noh play performed at celebratory occasions such as New Year’s and the opening of a stage, praying for peace and prosperity throughout the land. It possesses unique characteristics that set it apart from other Noh plays. Considered especially “exceptional” even among Noh performances, it is revered by Noh actors as a sacred piece, often described as “Noh, yet not Noh.”

The words of the chant (謡 / utai)* are almost like incantations, and since ancient times, it has been highly valued as something akin to a Shinto ritual.

*Utai (謡): Refers to lines and songs that are chanted or sung by voice.

“Takasago” (高砂)

In the early Heian period, a Shinto priest visits the shore of Takasago and hears from an elderly couple about the origin of the “Aioi-no-Matsu”* (相生の松) of Takasago and Sumiyoshi. The couple reveals themselves to be the spirits of the pine trees and, saying they will wait at Sumiyoshi, depart by boat. Later, when the priest visits Sumiyoshi, the deity Sumiyoshi Myojin appears before him, performs a dance, and blesses him with longevity and peace.

“Takasago” is one of the most prestigious plays among the waki Noh repertoire and is widely beloved as an auspicious piece often performed at weddings and celebrations.

*Aioi-no-Matsu (相生の松): Pine trees that appear to grow together from a single root, symbolizing harmony and unity.

“Hagoromo” (羽衣)

At Miho no Matsubara, a fisherman finds a celestial maiden’s feathered robe (羽衣 / hagoromo) and tries to take it home. The celestial maiden desperately pleads for its return, but the fisherman replies, “I will return it if you show me a dance.” Eventually, the maiden, wearing her feathered robe, performs a mysterious and graceful dance known as “Hagoromo-gaeshi,” showers treasures from the heavens, and ascends to the celestial realm.

The celestial maiden’s dance in the latter half is known as one of the most famous scenes in Noh, evoking a sense of nobility and ethereal beauty in the audience.

Representative Works of Kyogen

“Sambaso” (三番三 or 三番叟)

This is the role performed by a Kyogen actor in the latter half of the Noh play “Okina.” Sambaso is often performed at celebratory occasions, and has been passed down as a dance praying for a bountiful harvest and peace throughout the land.

One of the dances is “Momi-no-dan” (揉ノ段), where the performer stamps their feet powerfully in time with the drum. Another is “Suzu-no-dan” (鈴ノ段), in which the performer, wearing the Kokujiki (黒式尉) mask and holding bells, mimics sowing seeds while gradually increasing the tempo. Both dances are prayers for a good harvest, and the movements and notations may differ depending on the school.

“Boushibari” (棒縛)

Taro Kaja and Jiro Kaja (次郎冠者) are always sneaking drinks while left in charge of the house. To prevent them from drinking, their master ties one to a pole and binds the other’s hands behind his back. However, the two work together in a comical struggle to drink anyway, and eventually start a party.

This popular Kyogen play is known for its humorous depiction of the two dancing and chanting while still tied up, delighting audiences with its physical comedy and witty exchanges.

Places and Venues to Enjoy Nohgaku

Nohgaku can be enjoyed at Noh theaters throughout Japan, including the National Noh Theatre in Sendagaya, Tokyo. There are also many traditional venues such as the Kyoto Kanze Kaikan in Kyoto and the Ohtsuki Noh Theatre (Kongo Noh Theatre) in Osaka, each offering unique regional performances.

Additionally, “Takigi Noh” (薪能), outdoor Noh performances held at shrines, temples, or open-air stages, are highly recommended. The stage illuminated by bonfires creates an even more mystical atmosphere, making for a truly special experience.

How to Enjoy Nohgaku at Home

The most practical way to enjoy Noh and Kyogen at home is through DVDs/Blu-rays of recorded performances or official streaming and archive videos from theaters. By using authorized streams instead of unauthorized uploads, you can enjoy high-quality video and audio with peace of mind, while also supporting copyright protection.

To create the right viewing environment, dim the room lights and use indirect lighting to evoke the atmosphere of the stage. Using speakers or headphones to reproduce the sound of the musical accompaniment and chanting will further enhance the sense of presence.

For pre-performance study, take advantage of online explanatory videos, stage commentaries with archives, and audio chant books (謡本 / utaibon) provided by Noh theaters and schools. This will deepen your appreciation when attending live performances.

Comments