Japan has a rich natural environment, with diverse cultures, dialects, and food customs visible across each region. Of these varying regions, Kanto and Kansai are often compared. So, here is a brief introduction to the differences in food culture between the Kanto and Kansai regions!

* If you purchase products or make reservations through links in this article, a portion of the sales may benefit FUN! JAPAN.

🚅Book your Shinkansen ticket with NAVITIME Travel! 👉 Click here

▶Enjoy a more convenient trip to Japan with NAVITIME eSIM!👉 Click here

What are the Kanto and Kansai regions?

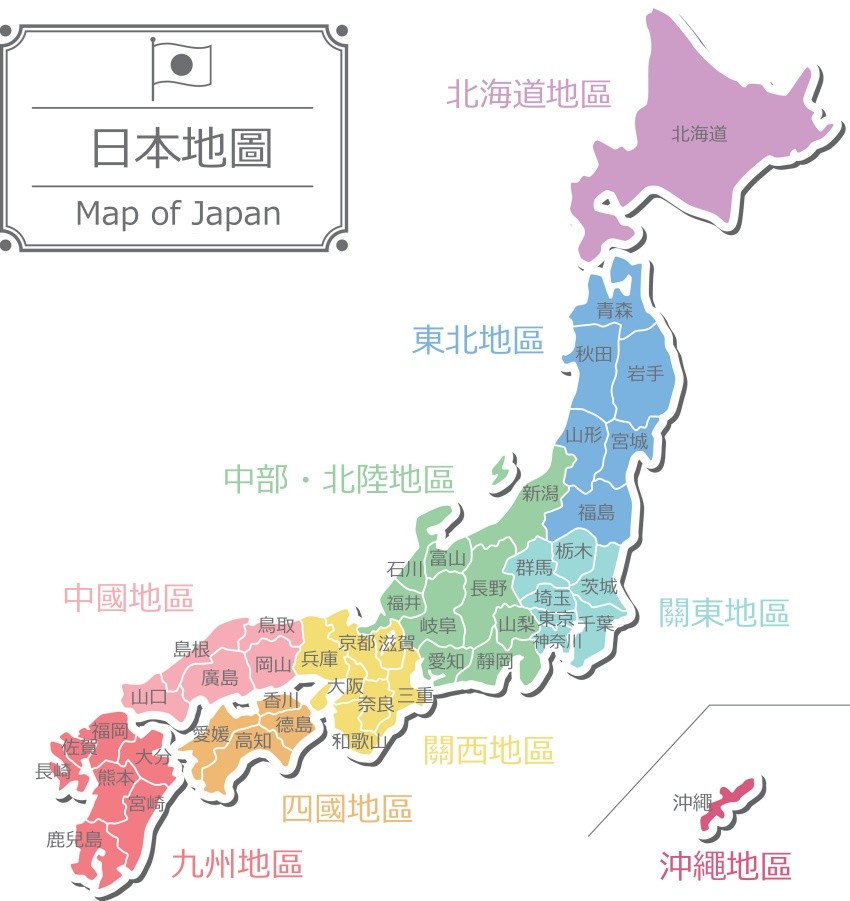

The Kanto region is made up of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, Saitama, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, and sometimes Nagano and Yamanashi prefectures. The Kansai region is made up of Osaka, Kyoto, Hyogo, Shiga, Nara, Wakayama, and Mie prefectures, and sometimes Shikoku as well.

Kanto people like soba, Kansai people like udon?

Soba and udon noodle dishes can be found in every region of Japan, and both are considered Japanese soul food.

There is a saying in Japanese food culture that translates to “Soba in the East, Udon in the West", describing how there are more soba restaurants in Kanto, the East, and more udon restaurants in Kansai, the West. However, there is also a difference in the way ‘dashi’ (soup stock) is prepared in both regions. In Kanto, dashi is often seasoned with bonito flakes and dark soy sauce, making the stock darker in color and stronger in flavor. In contrast, dashi in Kansai is mainly made from kombu kelp and is characterized by its relatively clear color.

Is there a difference in the way unagi is prepared in the Kanto and Kansai regions?

The origin of ‘unagi’, or eel cuisine, dates back to Japan’s Edo period (1603 – 1867), when it was developed as a dish loved by the common people. Here again, it’s possible to see a marked difference between food cultures of Kanto and Kansai.

Because the samurai capital ‘Edo’ (Tokyo) was part of the Kanto region, the way eels were cut was sometimes associated with the act of ‘seppuku’ - a form of ritual disembowelment that was considered major taboo for samurai. This may be why it has become commonplace for eels in the Kanto region to be handled from the back. In contrast, Osaka, in the Kansai region, has long been a thriving commercial center, and Osaka merchants were expected to be honest and trustworthy. Eels in Osaka are prepared belly-up, as it was believed that was the sincerest way to cut the fish, amongst other theories.

Intriguingly, there are also differences in cooking methods. In the Kanto region, eels are steamed and then grilled, creating a tender, fluffy fillet to which a thick sauce is added. However, in Kansai, raw eel is simply grilled, creating a firmer texture. The sauce is also not as thick as in the Kanto region.

The differing forms of ‘Inari’ sushi: Kanto's rectangular shape vs. Kansai's triangle shape

If you have previously visited Japan, you may have come across the widely loved dish of Inari sushi – sushi rice wrapped in sweet, deep-fried tofu. However, did you know that Kanto Inari sushi is rectangular, whereas Kansai Inari sushi is triangular? Which type have you tried before?

One theory behind the triangular shape of Inari sushi in Kansai is that it is shaped like Mount Inari, where the Fushimi Inari Taisha, the main shrine of Inari Shrine, is located. Another theory suggests the triangles represent the the ears of a fox – the animal considered messengers of the god Inari. Both theories have not yet been proven, but it adds an extra layer of mystery to this seemingly simple Japanese food staple!

Number of Mitarashi dumplings: 4 in Kanto vs. 5 in Kansai

In the Kanto region, there are four bite-sized pieces served on each skewer, whereas in the Kansai region, five slightly smaller dumpling balls are stacked on each skewer. The birthplace of skewered ‘dango’ dumplings is the ‘Kamo Mitarashi Tea House’ at Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto. Each 5-piece skewer represented the head and limbs of a person and was originally offered to the gods to pray for blessings and to prevent natural disasters and accidents.

Later, dumplings spread to Edo (present-day Tokyo), where the sweet treats became the most popular confectionery in the region. During the early days in Edo, it was the norm to make five pieces per skewer, which were then sold for 5 ‘sen’ each. However, in the mid-18th century, with the introduction of the New Currency Act, merchants switched to four pieces per skewer for easier calculation, and these became the new norm, continuing to the present day.

In other regions, ‘dango’ with three dumplings per skewer are also found. The most typical of these is the ‘sanshoku dango’ (three-colored dumpling), an essential part of hanami (cherry blossom viewing). The white, pink, and green dumplings are said to represent the seasons of winter, spring, and summer, respectively: snow white, cherry blossoms, and fresh greenery.

Oyakodon seasoning: Kanto's shichimi vs. Kansai's sansho

When you eat oyakodon (chicken and egg rice bowl) at a Japanese restaurant, have you ever noticed the various condiments placed on the table? Usually, customers are encouraged to enjoy the original taste of oyakodon first, and then enhance the flavor with the supplied condiments and pickles. Generally, there are two types of condiments used: shichimi (Japanese seven spices) or sansho (Japanese pepper). Sansho is famous in Kyoto, and is used not only in oyakodon, but in all kinds of Kyoto cuisine. In Tokyo, shichimi takes center stage.

There are also key differences in the ingredients used for oyakodon in Kanto and Kansai. Kanto style oyakodon usually consists of onions, chicken, and eggs, and is seasoned with a soy sauce base. Kansai-style oyakodon, however, uses green onions, chicken, and egg, and is seasoned with dashi broth.

Has this deep dive into Japanese food culture got your appetite going? Next time you eat Japanese food, why not try to distinguish the difference between Kanto and Kansai? Itadakimasu! (Let’s eat!)

*Because many theories on Japanese food culture exist, the information presented in the article should only be regarded as a rough guide.

🚅Book your Shinkansen ticket with NAVITIME Travel! 👉 Click here

▶Enjoy a more convenient trip to Japan with NAVITIME eSIM!👉 Click here

Comments